Most trade and development in the colonies is conducted by private Trading Companies or Merchant Houses. Some of these are sponsored or partly funded by their respective governments, some are public stock companies, some are privately subscribed stock companies and some are family held companies. The largest are either government sponsored or public stock companies. Their success is often the result of exclusive trading rights to a given area or set of goods. Such exclusivity is generally limited to the sponsoring nation. For example, the English Crown grants exclusive trade rights in India to the East India Trading Company, that does not mean that the French will recognise and accept that grant.

There are literally hundreds of these companies, but the biggest, richest and best known are these nine.

Coin of the Dutch East Indies Company

The Dutch East Indies Company

Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC was established in 1602

By 1669, the VOC was the richest private company the world had ever seen, with over 150 merchant ships, 40 warships, 50,000 employees, a private army of 10,000 soldiers, and a dividend payment of 40%

Most of the VOC’s activities and resources are in the Pacific, where it is in frequent competition with the British East India Trading Company. VOC ships do travel to the Caribbean on occasion, though most Caribbean pirates will encounter VOC ships along the coast of Africa as they are working their way south around the Horn.

Dutch West Indies Company

Dutch West India Company (Dutch: Geoctroyeerde Westindische Compagnie or GWC) in English the Chartered West India Company 1621 – 1793 was a company of Dutch merchants. Among its founding fathers was Willem Usselincx (1567-1647?). On June 3, 1621, it was granted a charter for a trade monopoly in the West Indies (meaning the Caribbean) by the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands and given jurisdiction over the African slave trade, Brazil, the Caribbean, and North America. The area where the company could operate consisted of West Africa (between the Tropic of Cancer and the Cape of Good Hope) and the Americas, which included the Pacific Ocean and the eastern part of New Guinea. The intended purpose of the charter was to eliminate competition, particularly Spanish or Portuguese, between the various trading posts established by the merchants. The company became instrumental in the Dutch colonization of the Americas.

The GWC was organized similar to the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) United East India Company commonly known as the Dutch East India Company 1602 – 1798, which had a trade monopoly for Asia (mainly present Indonesia) since 1602, except for the fact that the GWC was not allowed to conduct military operations without approval of the Dutch government. Like the VOC, the company had five offices, called chambers (kamers), in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Hoorn(all in Holland), Middelburg (in Zeeland) and Groningen (in the north), of which the chambers in Amsterdam and Middelburg contributed most to the company. The board consisted of 19 members, known as the Heeren XIX (the Lords Nineteen).

The company was granted the monopoly of the trade with America and Africa and between them, from the Arctic regions to the Straits of Magellan, and from the Tropic of Cancer to the Cape of Good Hope. The policy the company proposed to follow was to use its monopoly on the coast of Africa in order to secure the cheap and regular supply of negro slaves for the possessions it hoped to acquire in America. The trade was thrown open by the voluntary action of the company in 1638. The general board was endowed with ample power to negotiate treaties, and make war and peace with native princes; to appoint its officials, generals and governors; and to legislate in its possessions subject to the laws of the Netherlands. The states general undertook to secure the trading rights of the company, and to support it by a subvention of one million guilders. In case of war the states-general undertook to contribute sixteen vessels of 300 tons and upwards for the defence of the company, which, however, was to bear the expense of maintaining them. In return for these aids the states-general claimed a share in the profits, stipulated that the company must maintain sixteen large vessels (300 tons and upwards) and fourteen “yachts” (small craft of 50 to 100 tons or so); required that all the company’s officials should take an oath of allegiance to themselves as well as to the board of directors; and that all despatches should be sent in duplicate to themselves and to the board.

The company was initially relatively successful; in the 1620s and 1630s, many trade posts or colonies were established. The New Netherland area, which included New Amsterdam, covered parts of present-day New York, Connecticut, Delaware, and New Jersey. Other settlements were established on the Netherlands Antilles, several other Caribbean islands, Suriname and Guyana. The largest success for the GWC in its history was the seizure of the Spanish silver fleet, which carried silver from Spanish colonies to Spain by Piet Heyn in 1628; privateering was at first the most profitable activity. In 1630, the colony of New Holland (capital Mauritsstad, present-day Recife) was formed, taking over Portuguese possessions in Brazil. In Africa, posts were established on the Gold Coast (now Ghana) and briefly in Angola. In the Americas, fur (North America) and sugar (South America) were the most important trade goods, while African settlements traded slaves—mainly destined for the plantations on the Antilles and Suriname—gold and ivory.

This chain of successes quickly ended, however. New Holland was lost to Portuguese Brazil in 1654, after a long war, and many other trading posts were also destroyed or captured by rivalEuropean nations. The New Netherland colonization effort did not spread further either, in part due to a fierce rivalry with the English, who conquered New Netherland in 1664, and in part due to the difficulty of attracting settlers under the company’s initial policy of the Patroon system, which granted vast power over settlers to the men who brought them to the colony. After years of debts, the original GWC folded in 1674, and a new, reorganised company was formed. Piracy was abandoned, and the company concentrated mainly on the African slave trade and its remaining possessions in Suriname and the Antilles.

Compagnie des Indes Occidentales

French West India Company (Compagnie des Indes Occidentales) was a chartered company established in 1664. The charter gave them the property and seignory of Canada, Acadia, the Antilles, Cayenne, and the terra firma of South America, from the Amazon to the Orinoco. They have exclusive privilege for the commerce of those places, and also of Senegal and the coasts of Guinea, for forty years, only paying half the duties. The stock of the company was considerable, in less than 6 months, 45 vessels were equipped; with which they took possession of all the places in their grant, and settled a commerce.

In 1674, the FWIC was in financial trouble caused by its losses in the wars with England, which had necessitated it to borrow large sums; and even to alienate its exclusive privilege for the coasts of Guinea. The Crown briefly suspended its trading privileges and the Company reorganised itself and surrendered its exclusive rights to Canada and Guinea in exchange for fresh investments.

The FWIC is a presence in the Caribbean but seems to have reached its maximum potential in terms of growth and is beginning to loose ground in many places. The losses in the last war have taken their toll and FWIC warehouses are rarely filled to capacity.

Compagnie des Žles de l’Amérique

The Compagnie des Žles de l’Amérique, (Company of the American Islands) A French chartered company which colonized the Caribbean islands of Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint-Christophe island (present day Saint Kitts and Nevis.)

This French company controls all trade in and out of its home islands. The Governors of the islands are appointed and employed by the Company and the Company maintains miltia, custom guards and an armed Sloop for defense. The Company has also been a regular employer of privateers and pirates as supplementry defense forces during time of war.

Though officially anti-piracy, the Governors have been known to look the other way, in exchange for a generous gift, when pirate ships have put into port to sell their cargo.

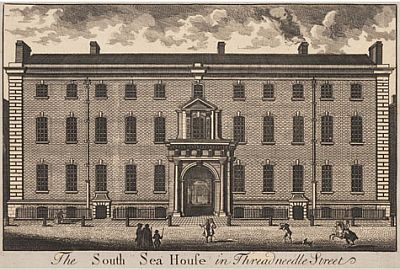

Headquarters of the South Sea Company

South Sea Company

The South Sea Company, founded in 1711 is an English company granted a monopoly to trade slaves with South America under a treaty with Spain.

The SSC is a high profile company that has attracted a lot of money and interest. Its shares are very valuable and its agents are aggressively trying to expand its presence in the Caribbean. At present the SSC is legally allowed to send six shiploads of slaves to designated ports in New Spain. This licensed trade is being leveraged into a larger trading presence for the entire Caribbean. The SSC’s goal is to become the Caribbean’s version of the HEIC while at the same time it is being developed as a financial instrument of the British Government.

Honourable East India Company Flag

Honourable East India Company (HEIC)

The Honourable East India Company (HEIC), often colloquially referred to as “John Company”, was the first joint-stock company (the Dutch East India Company was the first to issue public stock). It was granted an English Royal Charter by Elizabeth I on December 31, 1600, with the intention of favouring trade privileges in India. The Royal Charter effectively gave the newly created HEIC a 21 year monopoly on all trade in the East Indies.

In 1609, the King renewed the charter given to the Company for an indefinite period, including a clause which specified that the charter would cease to be in force if the trade turned unprofitable for three consecutive years.

The Company is led by one Governor and 24 directors who made up the Court of Directors. They are appointed by, and reported to, the Court of Proprietors. The Court of Directors has ten committees reporting to it.

The HEIC is huge! It rivals the VOC in ships, troops, revenues and extant. Like the VOC its primary area of interest is in the Pacific and East and most Caribbean pirates will encounter HEIC ships along the coast of Africa. However, HEIC ships do make call, once in awhile, in the Caribbean.

Royal Africa Trading Company

The Royal Africa Company, known colloquially as the Guinea Company because it trades on the Guinea Coast, from Gambia to the mouths of the Niger. It was established in the early 1660s to deal in gold and ivory, but is now mainly engaged in the slave trade. Granted Royal Charter 1672.

Guinea Company ships trade primarily with the North American Colonies and Jamaica. They are not welcomed (officially) in Spanish ports.

Gold from the Guinea coast was used to mint an English coin called a guinea, equivalent in value to a pound of silver. In reference to the ivory trade an elephant was incorporated into the design of the coin.

Hudson Bay Company

In 1670, the “Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson’s Bay,” better known as the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), was created. With its charter, the King of England granted the HBC an exclusive right to trade in the huge territory known as Rupert’s Land. Named after Prince Rupert, one of the principals in the company, Rupert’s Land is a vast area of about 7,770,000 km² and encompasses all the land that is drained by rivers flowing into Hudson Bay — in short, much of what is now western and northern Canada. In return, the company is expected to give the British monarch two elk and two black beaver whenever a royal visit was made to the territory.

HBC has a small trading fleet of ten or twelve ships. They tend to the small side since they are expected to travel up river from the Bay.

La Casa de Contratación Bandera_de_Espana 1701

La Casa de Contratación

La Casa de Contratación (The House of Trade) is a government agency under the Spanish Empire from the 16th century, which controls all Spanish exploration and colonization. Its official name is La Casa y Audiencia de Indias. La Casa collects all colonial taxes and duties, approves all voyages of exploration and trade, maintains secret information on trade routes and new discoveries, licenses captains, and administers commercial law. In theory, no Spaniard can sail anywhere without the approval of La Casa, but in reality corruption and smuggling are common. A 20% tax (the quinto) is levied by La Casa on all goods entering Spain, but other taxes can run as high as 40% in order to provide naval protection for the trading ships. Each ship is required to provide a clerk who keeps detailed logs of all goods carried and transactions undertaken.

La Casa is huge! Not as big (anymore) as the VOC is or the HEIC, but still very formidable and is spread over a wider geographic area then the other two. La Casa is rumored to have an extensive spy network, including many non Spanish agents, scattered throughout New Spain, the Caribbean, the Pacific, parts of the North American Colonies and much of Europe. They are, reputedly, not above sabotage and other nastiness to smother rival companies and punish disobedient Spanish captains. They serve both the La Casa’s interest and the Crown’s.

Casa da India

The parallel Portuguese organization, the Casa da India, or House of India of Lisbon is actually older then La casa, it was established in the 1400s. Its goals, objectives and methods are virtually identical to Spain’s La Casa, at one time the two organizations were united but split with Portugal’s independence. Now the Casa da India and La Casa are bitter rivals and spend much of their energy trying to out do each other. Casa da India operates both in the Pacific, India and along the South American coast.